What he was

Once upon a time, I wouldn’t even have to answer this question. He was such a famous, beloved guest of television hosts like Ed Sullivan that everyone knew who he was. Even people like me, who weren’t alive back then, knew who he was by all of the cultural references. But for the sake of you poor souls who’ve never heard of him, I’ll give a brief summary and then move on to the main focus of today’s article.

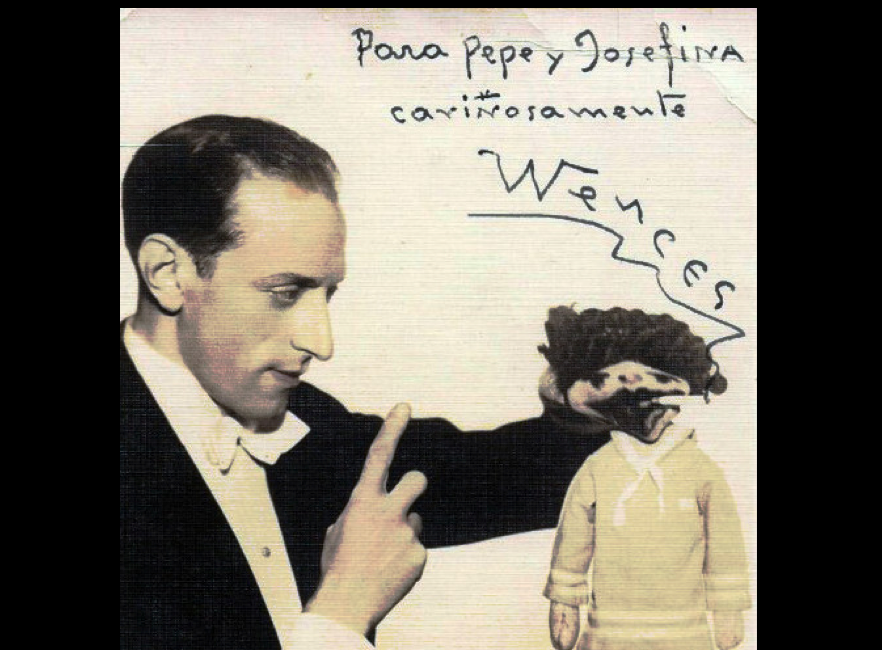

Wenceslao Moreno, later going by the name Señor Wences, was a ventriloquist and showman. Though he used a few puppets, he was most famous for a hand puppet named Johnny and for his feats of technical acumen like carrying on a conversation with his puppets while spinning plates on the ends of sticks, or drinking and smoking.

You have to keep in mind that the Internet hadn’t been invented yet, and this was the sort of thing that people paid money to see.

Now, I want to preface this explanation by saying that I only intend to write about his early life in Spain. He spent most of his adult life in the United States, but that’s hardly relevant to a column about Spain, so I’ll focus here solely on his youth in the province of Salamanca. Despite his fame, it was surprisingly hard to find much information about this part of his life, so I had to carry out a lot (I didn’t keep track, but it was easily dozens–if not hundreds–of seconds) of independent research using my fluency in archaic Spanish as well as sources of unfortunately dubious validity in order to fill in the blanks. With that in mind, and with the expectation that a few of the details will be mixed up (not because of mistakes I’ve made in translating them, but because of errors in the source material), I hope you’ll find the story of Señor Wences’ early period as fascinating as I did. I will conclude, as usual, with some thoughts on what I like and dislike about the man, as well as offer my expert opinion on how he could be improved, were he not already dead.

How he was made

Chapter 1

Señor Wences was born Wenceslao Moreno in 1896 in Peñaranda de Bracamonte. His father, Antonio Moreno Ros, was a miller by trade. Like many men his age, Antonio was called into military service to fight for the King in the Disaster of ’98 in Cuba, where he senselessly perished.

To avoid destitution, Wenceslao’s mother, Josefa Centeno Lavera, went to work as a maidservant for the wife of a wealthy merchant. This life was very idyllic, and though he often had to stay in the stables and amuse himself by talking to the animals or his own hands, who he’d named «Johnny» for amusement, Wenceslao was by all accounts quite happy with this arrangement.

Whenever the merchant travelled on business–which was quite often–his wife and Josefa would make plans with their boyfriends. Wenceslao had not been old enough to sense anything untoward about this arrangement, nevertheless his mother would swear him to secrecy and tell him to stay in his stables no matter what he heard, sealing the bargain by giving him some of the fine foods and desserts the men would bring as gifts for their ladies. Wenceslao would accept these delicacies eagerly and scamper off to share them with the livestock.

One day (this was around 1902), a 20-something man knocked on the post of the stable (despite the door being quite open), and introduced himself. He was a student on his way home and asked the merchant’s wife if she had a place for him to sleep for the night. Being a kind woman, but forgetting about Wenceslao, she graciously offered him the stables. The boy cautiously greeted him back, and then resumed speaking to a mule about the dismal state of affairs in France. Intrigued, the student asked him if he and the mule understood each other, to which Wenceslao replied, «Certainly.»

The student said that he too had learned some things at the university, and that if he wanted, they could trade skills. Wenceslao asked him what he knew, and the student began listing all of the talents he had learned deep in the cave below the school where all of the really important knowledge was heavily guarded: making objects far away speak with your own voice, defying gravity by spinning things on top of slender poles, you name it. The promise of having all of those powers was irresistible to the young boy, and he gladly agreed.

No sooner had their eruditive transaction completed than the merchant came home early and quite unexpectedly. From his window in the stable, Wenceslao could see him driving the two pantsless men out of his home, kicking and swiping at the air behind them with his hat as they pulled up their trousers and fled. The merchant’s wife and Wenceslao’s mother came out and took a proper beating, and as he watched his mother lay on the ground crying and protecting her face with her hands, Wenceslao wished the student had taught him how to defend himself. He balled his tiny little hands into fists, prepared to defend his mother from the attacks, when he heard a sound. Wenceslao looked down at his left fist. It stared back at him and shook itself side to side as if to say, «No.» Then it spoke.

«Don’t do it, Wenceslao!» it said in a high-pitched–some might say annoyingly so–voice.

«Why not?» the boy replied.

«Run away, Wenceslao.» his right fist chimed in. «We will take care of you.» The left fist nodded in agreement.

Wenceslao looked up at the student, who shrugged his shoulders. «I’m a baccalaureate, Wenceslao. That means I know almost everything, but not quite.»

Completely convinced by these three watertight arguments, and completely consistent with the relationship he had with his mother until this point in the tale, Wenceslao stood up and ran out of the stable. He wasn’t sure yet where he was headed, but anywhere was better than this place with which he had been perfectly content up until this point…

**

Next week: Señor Wences II