What cinematographic influences do you have when you record a videoclip? Personally, when I see it, it comes to my mind cinematographers like Guy Maddin, Jan Svankmajer and even Walt Disney.

That’s very kind of you to say so! It might sound odd but I really don’t have any specific cinematographic in mind when I splice together a video, it’s more about creating a sustained atmosphere from what I have available to accompany the music. In this way I quite often imagine the MWC videos as a form of ‘pop art’ collage such as Richard Hamilton’s Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?. I’m not suggesting I’m in that linage, but that specific artwork often pops into my mind when I’m splicing things. Rather than just using ‘horror’ imagery, I like to have elements of odd children’s television and light entertainment shows ~ ‘Summer Dance Specials’, that kind of thing. In some ways closely-choreographed dance routines by besuited performers around a stately home can appear more unusual and peculiar than ‘here-are-some-skulls-and-a-demon’. And I much prefer to take something out of context than replicate the original intention.

One thing not to lose sight of, is that if you put just aboutany instrumental electronic track under archive film footage it’s difficult notto make it look good! One strong association I have is of watching Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriske Pointin the 90s with the sound off (sorry Pink Floyd) and Luke Slater’s 7th Plain ‘The Four Cornered Room’ on instead. When the end scene (and best bit) happens ~ a mountain side villa exploding in slow motion ~ the action mirrored the music perfectly.

I suppose if you are influenced by archive television in the music that you make, and you then use archive television to accompany that music, there is inevitably going to be some level of synchronicity. I’d also suggest the sheer quantity of archive film and television I’ve watched must have some effect ~ if you soak all of this stuff in something is bound to come out in your artistic endeavours. Also it’s great fun to splice a video together!

Women are the dominant characters in Clinkskell. Some time ago, you said that you “wanted to portray a positive female image in control is that when you’re tied in with the darker side of things, you have horror film connotations, and as you’re well aware, horror films generally have a pretty dodgy view as “women=victim.” Is there any film that inspired you to carry out this reverse proposal that you point out? Because it looks like the main character of Michael Powell’s ‘Peeping Tom’ could be a woman.

Not one film in particular, it’s just that if you happen to like 60s / 70s / 80s horror films then you’ll quickly notice a trend towards ‘screaming female victims’ which can be a bit tedious and depressing, especially when the films of often very inventive and experimental in other areas. I’ve always thought this, and I’m sure a lot of other people have similar feelings. I’m not sure I’m that interested in an actual reversal of this archetype, more a new default setting ~ a strong, varied, fashionably-attired female cast and one or two token male characters in the background.

Likewise, I think your music has that feeling of being a type of electronic of feminine sensibility. I’m right?

You are! From it’s inception Clinkskell was devised as a matriarchal society. I never made a conscious decisionas such, it was intuitively the obvious, natural way of things and as such, it followed the music created there would have this as a basic tenant. There seemed to be little point in stating this as a ‘fact’ or displaying this as an ‘intention of the music’ (I’m not really a fan of overtly political music), but maybe, over time some folks would notice strong femininity was subtly (or maybe not so subtly) a defining part of the aesthetic.

I think that the visual concept of Clinkskell has a bipolar meaning of darkness for children, but people who listen to your music and see your covers, drawings and clips usually are adults. Do you try to search that inside boy/girl and bring it out with a shiver?

Not consciously, as I mentioned above I don’t really feel a massive disconnect between what I felt as a child and what I feel now. Obviously tastes and aesthetics mature and develop, but that sense of ghostliness or taste for the pleasingly unusual has always been with me.

Also quite often I’ve done some artwork or piece of music and think it’s quite gentle or even happy, but I get quite different reactions from that when folks see or hear it!

Personally I don’t really find the majority of ‘supernatural’ ideas actually scary,as in genuinely disturbing. It’s more of a comforting dreamworld escape from reality isn’t it? Some of the moments in everyday life that flicker past in an instant (odd reflections in windows, wet shoe-prints forming an unusual patten that almost spells out your name) can be the bits of the day that you dwell upon the most.

I think that since the 90s, electronic music has lost the enigma on its visual perspective. I remember visual concept of Electronic Body Music bands, post-punk/pop bands like Associates or Eyeless In Gaza, and, definitely, it’s very difficult to find that feeling in these times of fast food mega-communication, where no one looks to be surprised. It’s like your music and visuals have a slow tempo to focus on things, sounds and images, like in Edwardian times. Is it?

I’d pretty much agree with this. I’d suggest a lot of it is to do with the presentation of ‘niche’ music. Broadly speaking, for the past 10-15 years the release cycle of a new ‘electronica’ album artist seems to be 6 months of hype, followed by 12 months of rave and often ludicrous reviews (‘the most important musical act of the 21st century’ etc) followed by general disinterest (‘yeah, we’re over that now’) when their follow-up on a major-indie label emerges 2 years later. Often their style has changed to play catch-up with whoever is getting the new attention, and they’ve lost the elements that made them interesting in the first place.

So you have about 18 months to make a coherent statement on your musical offerings! Which seems quite stifling to me, creativity doesn’t really work this way ~ everything is on FFWD. I don’t subscribe to the notion that everyone has a reduced attention span, I think it’s more to do with labels understandably needing more money and journalists needing something fresh to write about. Obviously not new concepts, but I’d certainly suggest they’ve been accelerated in the 21st century ~ plenty of these new artists are presented as being ‘unique, ground-breaking, revolutionary’, but they can’tall be that original. So the constant re-iteration of the new ‘cutting-edge’ sound means you soon get tired of what’s being presented, and it’s easy to miss something that might be musically more interesting but perhaps doesn’t have the ‘correct’ PR behind it.

I had my 18 months with ‘A Spare Tabby at the Cat’s Wedding’, for a time in 2010-11 everything was ‘you are the greatest, please do this, what an original voice in music’etc, extremely flattering and much appreciated, but once the dust had settled, the majority of these people had no interest when my next album came out ~ and fair enough! The circus had moved on. Because I was fortunate enough to have slowly built up a fanbase since 2006, and even more importantly devised an artistic concept that I wouldn’t tire of (drawing vaguely aristocratic women in fancy hats), I could keep going without needing five star reviews and all the ‘correct’ attention or a depressing re-invention.

I’ve not specifically thought about MWC having an Edwardian tempo in terms of publicity, but I’d be more than happy to go along with that! In my own mind I think of the MWC album release schedule a bit like Agatha Christie novels in the 40s & 50s ~ once a year before Christmas, with variations on a theme but identifiable as part of one person’s creative mind.

In theory, ‘When A New Trick Comes Out, I Do An Old One’ is collected record of remixes, rarities and an unpublished album. It’s revealing that, being songs of different origins and years it sounds like an autonomous work. Did you conceive it as a corpus of the MWC sound?

I’m glad you think so! It wasn’t conceived as such, but there was a definite attempt to sequence everything in a coherent manner. There was about 36 hours of unreleased MWC music, and a lot of that was terrible, but there were several decent tunes that didn’t make it because they didn’t fit in properly on a 3xCD format. I’d say that if MWC music has an autonomous sound it’s because I spent years slowly figuring out what I wanted to sound like before releasing music into the wild. Certain elements may alter, but most of the ingredients remain the same because they are my favourites!

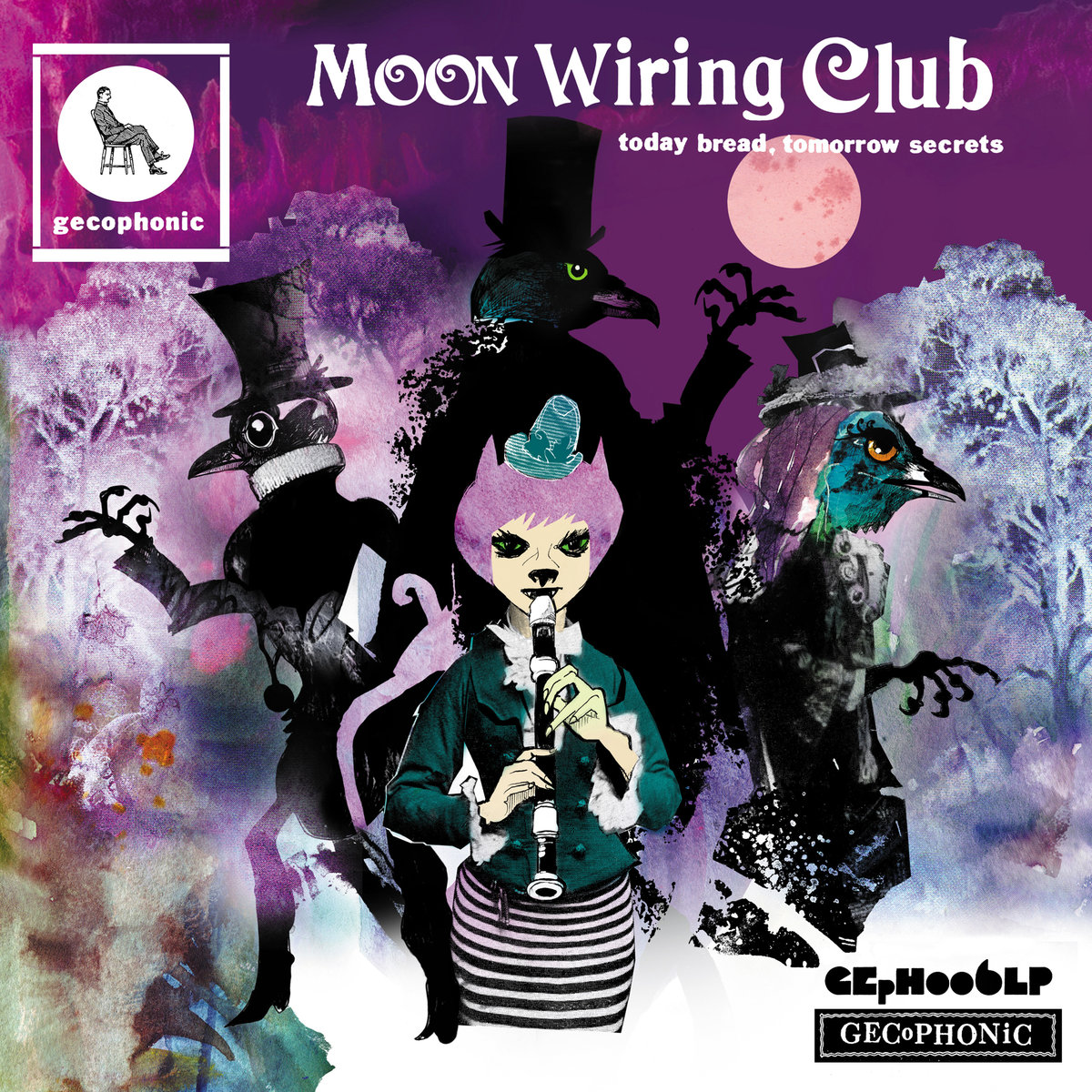

In the same way, I decided that the cover artwork should feature something I wouldn’t get bored of drawing. If the first CD went well, I thought how splendid it would be to have all the design elements replicated for the second. I knew I wouldn’t drastically change my sound (or indeed couldn’t), and I really liked the idea identifiable MWC aesthetics ~ like a favourite actor dressing up in different clothes for different films. I’d say MWC music has definitely progressed and altered over the years, but it hasn’t lost the basic elements that would make it appealing in the first place.

What importance does Jon Brooks have on the final outcome of the sound?

Jon is a tip-top craftsman, extremely dedicated to his artistry and it’s a bloomin’ honour to have him mastering MWC music. He’s exceptional in drawing out certain nuances and providing a uniformity to the sound ~ ‘adding a certain bounce’ we like to call it. Additionally there is the technical side of things, in order to get music released on vinyl you really do need someone who knows what they are doing to master it effectively ~ removing distorting frequencies etc. He’s also taught me a lot about actual production techniques. You need a good ear in the first place, but there a definitely certain things you can do to improve the sonics of the music, even if that music is pretty lo-fi in its application.

Of course there has to be something of merit in what I’m doing in the first place! You can’t just hand over something to a mastering engineer and expect them to make something sound like it’s suddenly come from a 1970s hi-spec studio. Finally, there is the finality aspect or handing the music over. Once Jon has it, the album is nearly finished, there can be no more tinkering, and I’m an obsessive tinkerer!

Este artículo es una versión extendida, sin cortes, del publicado en febrero de 2017 en O Estudio Creativo.